If Dunkirk were to point to a highlight in its history that is a moral moment of generosity and self sacrifice, the most important moment might be Dunkirk to Dunkerque Day, November 28, 1946, the effort of Dunkirk’s people to provide goods and donations for the stricken city of Dunkerque, France, after World War II. Dunkirk raised between $75,000 and $100,000— in today’s money an amount equal to $1,073,381 to $1,431,175.

This “miracle” was achieved by a unique coalition of persistent leadership in Dunkirk and marketing know-how by a NYC based relief organization led by Dunkirk native Charles Todd. Dunkirk’s leaders were presented with a plan, key leaders saw the importance of that plan, and those leaders united Dunkirk to carry it out.

Following the fall of Nazi Germany to Allied Forces, professional relief agencies formed to help distribute supplies to stricken countries, funded by the US government’s “National War Fund.” That funding source ended, and fundraising evolved. In 1946, Madame Denise Davey became co-chairperson of “American Aid for France. Inc.,” with General Eisenhower serving as “Honorary President” and ties with French Ambassador Henri Bonnet. Charles Lafayette Todd, a Dunkirk native who had served as public relations officer in the Army during the war, became national publicity director for the National Campaign of American Relief for France. He thought an event that would “capture the imagination” of ordinary people in America was needed, “a symbolic gesture which will bring out the national media and appeal to all.”* Todd suggested his own hometown of Dunkirk be the starting point, explaining how its working class nature, its adoption of the French city’s name, the presence of a harbor and fishing industry in both cities, the presence of industry next to vineyards—all these would be appealing.

ATTF leadership agreed, and Charles Todd traveled to Dunkirk in September of 1946 to meet with old friend Observer editor Walter Brennan. Brennan reacted positively to the plan, aware this could capture world attention and put Dunkirk on the map. He met that same day with City Attorney Joe Rubenstein, Chamber of Commerce secretary Roman Waite, and several others, to discuss the idea, and support for the plan grew. Brennan traveled to NYC with Rubenstein and Waite to meet with ATTF leadership, and Todd wrote a proposal for his board of directors “that the nationwide AATF fundraising campaign for 1946-47 be launched in the city of Dunkirk, N.Y. on Thanksgiving Day, Nov. 29.”* His proposal promised the presence of Ambassador Bonnet, Charles Boyer, and nationwide press coverage. Brennan wrote Observer editorials appealing to the people of Dunkirk, and Mayor Murray formed a committee to lead the plan. A contract was signed between the City of Dunkirk and AATF noting the responsibilities for city and agency, and at a mass meeting at the DHS auditorium on Eagle Street with civic, social, and fraternal organizations, Murray took the stage and pointed to various members in the audience, asking them to state what their groups would donate, and they did just that.

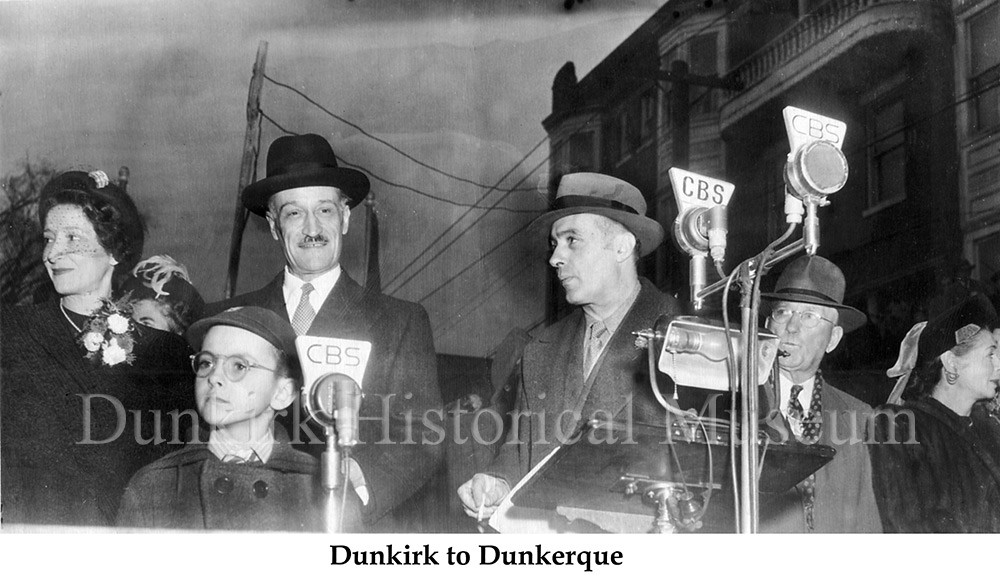

Donations flowed in, until November 28 arrived, and with it a contingent of dignitaries. Ambassador Bonnet arrived with French, British and Canadian military attaches from Washington, government reps, heads of French Veterans groups, and journalists from Life, Time, Newsweek, The Herald Tribune, and Colliers magazines, the AP, and CBS radio.

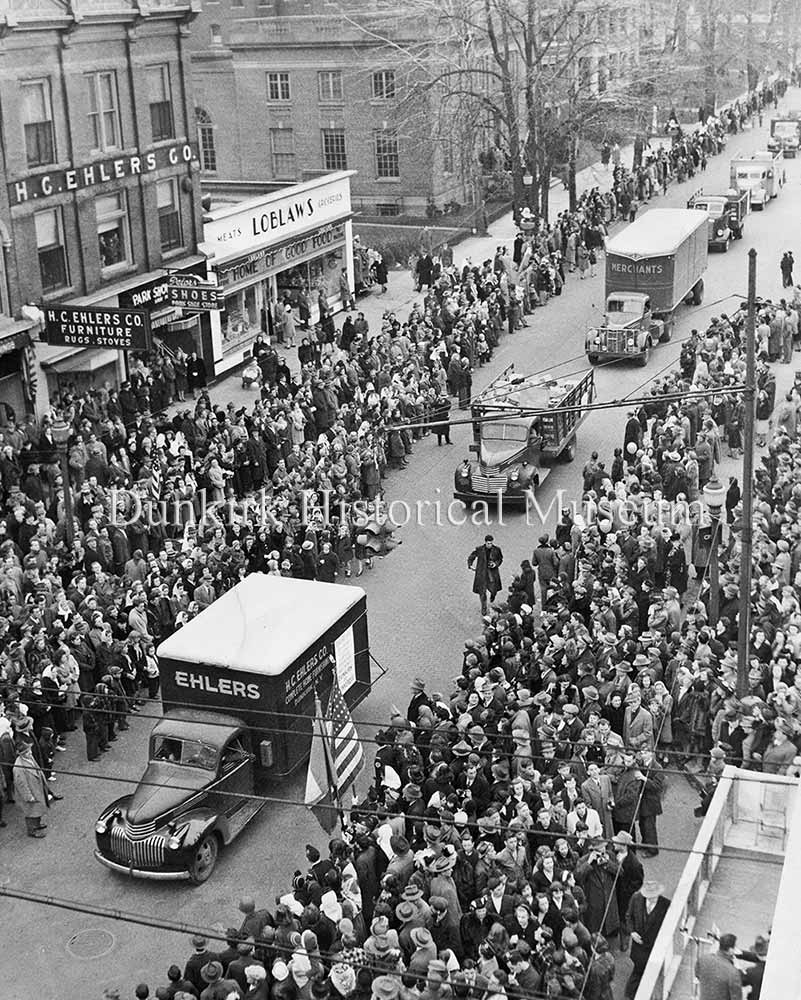

The day’s events included breakfast at Shorewood, ceremonies at Memorial Park, presentation of a plaque forged in a Dunkirk foundry to the Ambassador, and student performances at the high school auditorium on Eagle Street. At three, the mile long parade of gifts from some 100 organizations passed the review stand, including medical and dental supplies, clothing and footwear, a truck load of tools, canned food, blankets, plows and cultivators, livestock, as well as toys for the French children. That night at a dinner held at Floral Hall, Russell Davenport, publisher and writer, spoke. He declared “Dunkirk plus Dunkerque Equals One World”.*

This endeavor produced positive results. Dunkirk was showered with good will and praise from national papers and magazines, such as that from The Times Herald of Washington, who stated, “It is a veritable Tale of two cities. One of them famous and one of them that should be.” Elinor Roosevelt herself praised Dunkirk in her weekly column, “My Day.”

On the very night of the event Mayor Murray announced the formation of “The Dunkirk Society” to serve as an information center for cities wanting to follow Dunkirk’s lead. The group raised donations the following spring for Anzio, and then Polish city. Other US cities followed Dunkirk’s lead, gathering donations for European cities they paired with.

*Quote from manuscript of unpublished book written by Charles L. Todd, now part of the Dunkirk Historical Museum collection.